Category: Business,Blog

6 note taking systems you Should Master

What should we understand by note taking

Note taking is the practice of writing pieces of information, often in an informal or unstructured manner. One major specific type of note taking is the practice of writing in shorthand, which can allow large amounts of information to be put on paper very quickly. Notes are frequently written in notebooks, though any available piece of paper can suffice in many circumstances—some people are especially fond of Post-It notes, for instance.

Note taking is one of the major skills that you should master, either as a student, a journalist or even a researcher. Many different forms are used to structure information and make it easier to find later. It is important to note that, the way you take your note, might play a major role in your success in their use, academically for instance, or for any intended purpose.

Systems of Note taking

Cornell Notes

When using the Cornell note-taking system a column of white space is left to the left side of the notes that are written as they come up. Questions or key words based on the notes are written in the white space after the session has ended. The Cornell method requires no rewriting and yet results in systematic notes.

Charting

Charting is creating a graph with symbols, or table with rows and columns. Graphs and flow-charts are useful for documenting a process or event. Tables are useful for facts and values

Outlining

While notes can be written freely, many people structure their writing in an outline. A common system consists of headings that use Roman numerals, letters of the alphabet, and the common Arabic numeral system at different levels. A typical structure would be:

- First main topic

- Subtopic

- Detail

- Detail

- Subtopic

- Second main topic

- Subtopic

- etc.

However, this sort of structure has limitations in written form since it is difficult to go back and insert more information. In a way to make writing so comfortable, some adaptive systems are used for paper-and-pen insertions, such as using the back side of the preceding page in a spiral to note insertions.

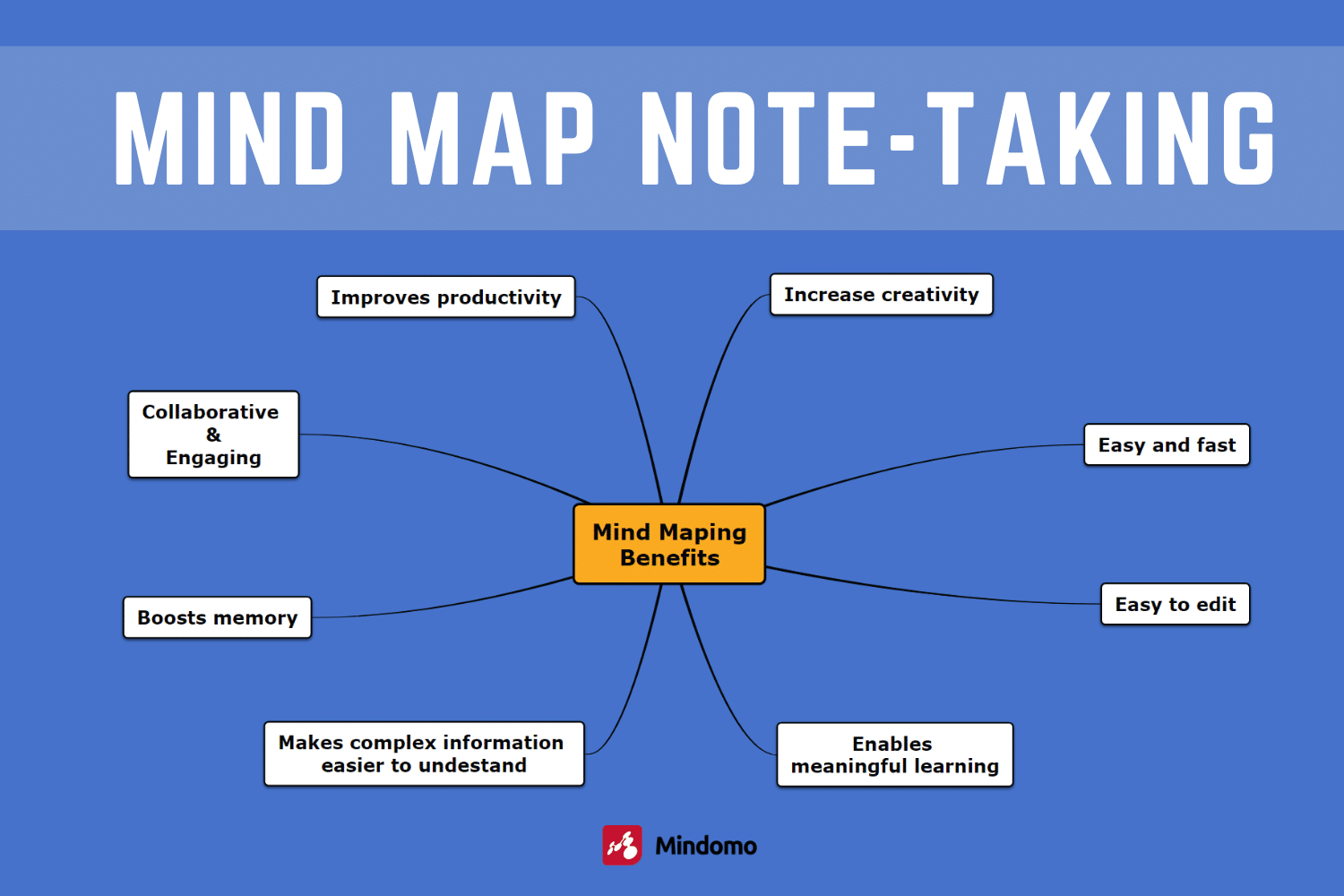

Mapping

Here, ideas are written in a tree structure, with lines connecting them together. Mind maps are commonly drawn with a central point, purpose or goal in the centre of the page and then branching outward to identify all the ideas connected to that goal. Colours, small graphics and symbols are often used to help to visualize the information more easily. This note taking method is most common among visual learners and is a core practice of many accelerated learning techniques. It is also used for planning and writing essays.

Sentence method

Every new thought is written as a new line. Speed is the most desirable attribute of this method because not much thought about formatting is needed to form the layout and create enough space for more notes. Also, you must number each new thought.

SQ3R System of note taking

SQ3R is a method for taking notes from written material, though it might be better classed as method of reading and gaining understanding. The term itself, is one of Cornell note taking techniques, which stands for Survey – Question – Read – Recite – Review (or Re-skim).

In order to use this method effectively, the reading material is skimmed to produce a list of headings, which are then converted into questions. These questions are then considered whilst the text is read to provide motivation for what is being covered. Notes are written under sections headed by the questions as each of the material’s sections is read. One then makes a summary from memory, and reviews the notes.

What should we understand by note taking

Note taking is the practice of writing pieces of information, often in an informal or unstructured manner. One major specific type of note taking is the practice of writing in shorthand, which can allow large amounts of information to be put on paper very quickly. Notes are frequently written in notebooks, though any available piece of paper can suffice in many circumstances—some people are especially fond of Post-It notes, for instance.

Note taking is one of the major skills that you should master, either as a student, a journalist or even a researcher. Many different forms are used to structure information and make it easier to find later. It is important to note that, the way you take your note, might play a major role in your success in their use, academically for instance, or for any intended purpose.

Systems of Note taking

Cornell Notes

When using the Cornell note-taking system a column of white space is left to the left side of the notes that are written as they come up. Questions or key words based on the notes are written in the white space after the session has ended. The Cornell method requires no rewriting and yet results in systematic notes.

Charting

Charting is creating a graph with symbols, or table with rows and columns. Graphs and flow-charts are useful for documenting a process or event. Tables are useful for facts and values

Outlining

While notes can be written freely, many people structure their writing in an outline. A common system consists of headings that use Roman numerals, letters of the alphabet, and the common Arabic numeral system at different levels. A typical structure would be:

- First main topic

- Subtopic

- Detail

- Detail

- Subtopic

- Second main topic

- Subtopic

- etc.

However, this sort of structure has limitations in written form since it is difficult to go back and insert more information. In a way to make writing so comfortable, some adaptive systems are used for paper-and-pen insertions, such as using the back side of the preceding page in a spiral to note insertions.

Mapping

Here, ideas are written in a tree structure, with lines connecting them together. Mind maps are commonly drawn with a central point, purpose or goal in the centre of the page and then branching outward to identify all the ideas connected to that goal. Colours, small graphics and symbols are often used to help to visualize the information more easily. This note taking method is most common among visual learners and is a core practice of many accelerated learning techniques. It is also used for planning and writing essays.

Sentence method

Every new thought is written as a new line. Speed is the most desirable attribute of this method because not much thought about formatting is needed to form the layout and create enough space for more notes. Also, you must number each new thought.

SQ3R System of note taking

SQ3R is a method for taking notes from written material, though it might be better classed as method of reading and gaining understanding. The term itself, is one of Cornell note taking techniques, which stands for Survey – Question – Read – Recite – Review (or Re-skim).

In order to use this method effectively, the reading material is skimmed to produce a list of headings, which are then converted into questions. These questions are then considered whilst the text is read to provide motivation for what is being covered. Notes are written under sections headed by the questions as each of the material’s sections is read. One then makes a summary from memory, and reviews the notes.

5 steps in Writing Process for Smart writers

Writing process is a pedagogical term that appears in the research of Janet Emig who publishedThe Composing Processes of Twelfth Graders in 1971. The term marks a shift from examining the products of writing to the composing process of writers.

This focus on process encourages composition students to see writing as an ongoing, recursive process from conception of the idea through publication. It asserts that all writing serves a purpose, and that writing passes through some or all of several clear steps. It was part of the general whole language approach. Writing process

Steps in writing process

Generally the writing process is seen as consisting of five steps. They are:

- Prewriting:planning, research, outlining, diagramming, storyboarding or clustering (for a technique similar to clustering, see mindmapping)

- Draft:initial composition in prose form

- Revision:review, modification and organization (by the writer)

- Editing:proofreading for clarity, conventions, style (preferably by another writer)

- Submittal:sharing the writing: possibly through performance, printing, or distribution of written material

These steps are not necessarily performed in any given order. For example, the skills used in the prewriting process can be applied any time by writers seeking ideas throughout the process. It is not necessary to go through each step for every writing project attempted. The steps make up a recursive process. The instructional theory behind the model is similar to new product development and life cycle theory, adapted to written works.

By breaking the writing cycle into discrete stages and focusing on strategies at each stage, it is hoped that writers will develop an appreciation for the process of seeing an idea through to successful completion in a logical way. Rather than presenting written works as acts of genius that emerge fully formed, they are shown as the result of several distinct and learnable skills.

Prewriting is the first step of the writing process, followed by drafting, revision, editing and publishing and is crucial to the success of any writing task, yet in writing instruction; it seldom receives the attention it deserves.

Motivation and audience awareness

Prewriting begins with motivation and audience awareness: what is the student or writer trying to communicate, why is it important to communicate it well and who is the audience for this communication? Writers usually begin with a clear idea of audience, content and theimportance of their communication; sometimes, one of these needs to be clarified for thebest communication.

Student writers find motivation especially difficult because they are writing for a teacher or for a grade, instead of a real audience. Often teachers try to find a real audience for students by asking them to read to younger classes or to parents, by posting writing for others to read, by writing a blog, or by writing on real topics, such as a letter to the editor of a local newspaper.

Choosing a topic

One important task in writing process is choosing a topic and then narrowing it to a length that can be covered in the space allowed. Oral storytelling is an effective way to search for a good topic for a personal narration. Writers can quickly tell a story and judge from the listeners’ reactions whether it will be an interesting topic to write about. Two types of pre-writing are: free writing and researching.

- When free writing, you write any and every idea that comes to mind when writing.

- Researching is another name for writing, which you get information from outside sources.

Gathering information

Several other methods of choosing a topic overlap with another broad concern of pre-writing, that of researching or gathering information. Reading (process) is effective in both choosing and narrowing a topic and in gathering information to include in the writing.

As a writer reads other works, it expands ideas, opens possibilities and points toward options for topics and narrowing of topics. It also provides specific content for the eventual writing. One traditional method of tracking the content read is to create annotated note cards with one chunk of information per card. Writers also need to document music, photos, web sites, interviews, and any other source used to prevent plagiarism.

Besides reading what others have written, writers can also make original observations relating to a topic. This requires on-site visits, experimentation with something, or finding original or primary historical documents. Writers interact with the setting or materials and make observations about their experience. For strong writing, particular attention should be given to sensory details (what the writer hears, tastes, touches, smells and feels).

While gathering material, often writers pay particular attention to the vocabulary used in discussing the topic. This would include slang, specific terminology, translations of terms, and typical phrases used. The writer often looks up definitions, synonyms and finds ways in which different people use the terminology.

Lists, journals, teacher-student conference, drawing illustrations, using imagination, restating a problem in multiple ways, watching videos, inventorying interests – these are some of the other methods for gathering information.

Discussing information

Discussing information after writing

After reading and observing, in the writing process, often writers need to discuss material. They might brainstorm with a group or topics or how to narrow a topic. Or, they might discuss events, ideas, and interpretations with just one other person. Oral storytelling might enter again, as the writer turns it into a narrative, or just tries out ways of using the new terminology. Sometimes writers draw or use information as basis for artwork as a way to understand the material better.

Narrowing the topic

Narrowing a topic is an important step of pre-writing. For example, a personal narrative of five pages could be narrowed to an incident that occurred in a thirty minute time period. This restricted time period means that the writer must slow down and tell the event moment by moment with many details.

By contrast, a five page essay about a three day trip would only skim the surface of the experience. The writer must consider again the goals of communication – content, audience, importance of information – but add to this a consideration of the format for the writing process. He or she should consider how much space is allowed for the communication and what can be effectively communicated within that space?

Organizing content

At this point, the writer needs to consider the organization of content. Outlining in a hierarchical structure is one of the typical strategies, and usually includes three or more levels in the hierarchy. Typical outlines are organized by chronology, spatial relationships, or by subtopics. Other outlines might include sequences along a continuum: big to little, old to new, etc.

Clustering, a technique of creating a visual web that represents associations among ideas is another help in creating structure, because it reveals relationships. Storyboarding is a method of drawing rough sketches to plan a picture book, a movie script, a graphic novel or other fiction.

Developmental acquisition of organizing skills

Developmental acquisition of organizing skills

While information on the developmental sequence of organizing skills is sketchy, anecdotal information suggests that children follow this rough sequence:

- sort into categories

- structure the categories into a specific order for best communication, using criteria such as which item will best work to catch readers attention in the opening,

- within a category, sequence information into a specific order for best communication, using criteria such as what will best persuade an audience. At each level, it is important that student writers discuss their decisions; they should understand that categories for a certain topic could be structured in several different ways, all correct.

- A final skill acquired is the ability to omit information that is not needed in order to communicate effectively.

Even sketchier is information on what types of organisation are acquired first, but anecdotal information and research suggests that even young children understand chronological information, making narratives the easiest type of student writing.

Persuasive writing usually requires logical thinking and studies in child development indicate that logical thinking is not present until a child is 10-12 years old, making it one of the later writing skills to acquire. Before this age, persuasive writing will rely mostly on emotional arguments.

Writing trials

Writers can also use the writing phase to experiment with ways of expressing ideas in the writing process. For oral storytelling, a writer could tell a story three times, but each time begin at a different time, include or exclude information, end at a different time or place. Writers often try writing the same information but using different voices, in search of the best way to communicate this information or tell this story.

Recursion

Writing is recursive, that is, it can occur at any time and the writing process can return several times. For example, after a first draft, a writer may need to return to an information gathering stage, or may need to discuss the material with someone, or may need to adjust the outline. While the writing process is discussed as having distinct stages, in reality, they often overlap and circle back on one another.

Variables

Writing process varies depending on the writing task or rhetorical mode. Fiction requires more imagination, while informational essays or expository writing require stronger organization.

Persuasive writing must consider not just the information to be communicated, but how best to change the reader’s ideas or convictions. Folktales will require extensive reading of the genre to learn common conventions. Each writing task will require a different selection of writing strategies, used in a different order.

Dependency Development

Introduction

Dependency development is an area of dependency theory which is mainly concerned with the efforts made to export primary resources from countries which are resource-rich but industry-poor. In this articles, we shall look at selected theories that emerged within the Neo-Marxist tradition. But before that it may be useful briefly to refer to the empirical background to the criticism raised against the original mainstream theories within both traditions.

Economic Situation in Developing Countries

First, it should be mentioned that the cumulated knowledge about the economic situation in the less developed countries had uncovered such a complex and multifaceted picture that it had become increasingly difficult to use the somewhat simplified conceptual framework and analytical models. In particular, it had proved impossible to conceive of the Third World as a large group of countries with uniform economic structures, development conditions and potentials. This applied where these countries were described as underdeveloped, as dual economies, as satellites, or as peripheral societies.

Next, it should be stressed that actual changes in the less developed countries in general implied greater and greater differentiation, accentuation of existing, and emergence of new, differences between the developing countries. To illustrate, they reacted and had to react in very dissimilar ways so the so-called oil crisis in 1973 and 1979, just as they reacted very differently to the continued stagnation in the world economy at the beginning of the 1980s. Because of this process of differentiation, it became increasingly inadequate to treat the Third World as a homogenous group of countries.

One of the few common traits that persisted was that economic progress almost everywhere remained limited to small geographic enclaves, to certain narrowly limited sectors, and so small prosperous social groups. The phenomenon has been characterized as `Singaporisation’, after the city state of Singapore, which, although surrounded by backward and poor areas, experienced unusual economic progress as early as the 1960s and 1970s.

However, even a common feature like ‘Singaporisation’ created problems for the classical theories, because it signified general tendencies very different from those envisaged in the theories. ‘Singaporisation’ corresponded poorly with the expectations of the modernization theories. It was contrary to these theories that development and modernization could be encapsulated and distorted to such a degree. Neither did this fit with the experiences garnered from the industrialised countries.

Limitations of the classical Dependency Theory

At the same time, the classical dependency theories were unable to explain the extensive industrial development which in fact occurred in many Third world countries. They faced particular problems when trying to understand and explain why, in countries like South Korea and Taiwan, even relatively close links had been forged between agriculture industry, and between the various industrial sectors.

This was in direct contradiction to the main thesis on the obstructing and blocking impact on close association with the world market and the rich countries: South Korea and Taiwan were among those countries most closely liked to the global capitalist structures and the centres of accumulation in the highly industrial countries.

These and many other factors prompted many development researchers and people who were actively engaged in development work to start looking seriously for other theories and strategies. The relatively closed theories, which at the same time treated the developing countries as a homogenous group had had their day. In their place appeared a number of more open theories which also, in a systematic manner, took into account the differences between the many countries of the Third World.

Many of these theories focused on specific aspects of reality, special development problems, and selected factors. One example could be proposition regarding the role of transnational companies in Latin American countries; another could be natural resource management in Western Africa and its impact upon economic performance.

The new wave of theories appeared partly as a criticism of the classical dependency theories; others took their point of departure in the modernization theories, but elaborated these considerably further, several of the new theories had little or more intellectual relationship or affinity with either or these two earlier schools of thought.

The Brazilian social scientist, F.H. Cardoso, was one of those who took his starting point in the original Latin American dependency theories (Cardoso and Faletto, 1979). However, he rejected the notion that peripheral countries could be treated as one group of dependence economies. In addition, he rebutted the idea that the world market and other external factors should be seen as more important than intra-societal conditions and forces, as some of these theories had asserted. Cardoso claimed instead that the external factors would have very different impacts, depending on the dissimilar internal conditions.

So decisive were the internal conditions, according to-Cardoso, that he would not rule out the possibility of extensive capitalist development in some dependent economies. Indeed, he did observe, in his own thorough analyses of Brazil that significant capitalist growth had occurred, though without creating auto centric reproduction and followed by marginalization of large segments of the population. When Cardoso referred to internal conditions, attention was drawn not only to economic structures but also to the social classes, t4ie distribution of power in the society, and the role of the state. His analyses thus reflected systematic’ attempts at combining economics and political science.

In contrast to Frank Cardoso regarded the national bourgeoisies of the dependence societies as potentially powerful and capable of shaping development. These classes could be so weak that they functioned merely as an extended arm of imperialism. But the national business community and its leaders, under other circumstances, as in the case of Brazil — act so autonornous/ and effectively that national, long-term interests were taken into account and embodied in the strategies pursued by the state.

The kind of development and societal transformation that could be brought about in even the most successful peripheral societies did not col respond to the development pattern in the centre countries. The result was not auto centric reproduction, but rather development in dependency (as opposed to Frank’s development of dependency). Or as Cardoso himself characterized it: dependent, associated development — that is development dependent on, and linked to, the world market and the centre economies.

In the further characterization of dependent development, Cardoso used, to a large extent concepts and formulations that resembled those of Amin. He thus emphasized the unbalanced and distorted production structure with its greatly over-enlarged sector manufacturing luxury goods exclusively for the benefit of the bourgeoisie and the middle class. Moreover, he high=lighted the absence of a sector that produced capital goods and the resulting dependency on machinery and equipment imports from the centre countries. But in contrast to Amin, Cardoso was very careful about generating. He would rather talk specifically about Brazil than about the peripheral countries in general.

In a similar way, Cardoso was reluctant to recommend general strategies, for a large number of dependent countries. Regarding Brazil, he pointed to a democratic form of regime as the most important precondition for turning societal development in a direction which would benefit the great majority of the people. Socialism was not on the agenda, and introducing it was in any case not as unproblematic as claimed by Frank and Amin.

Parallel to Cardoso’s efforts to adjust the classical dependency theories to the more! complex reality of Brazil, a number of German development researchers, under the leadership of Dieter Senghass and Ulrich Menzel, carried out a series of extensive historical studies of both centre and peripheral societies. The result was systematic and elaborate differentiation within both categories of counties. Their point was that when the centre countries were subjected to closer investigation, it turned out that they too, like the peripheral societies, revealed very different individualized structures and patterns of transformation. There were great differences for instance, between the Nordic and France or Germany.

Based on their historical studies Senghass and Menzel arrived at dissolution of the dichotomy between centre and periphery. In its place they put a number of patterns of integration into the world economy and the resulting development trajectories.

In addition, they reached the conclusion that the international conditions by themselves could not explain why a given society managed, or did not manage, so break out of the dependency trap. Far more important were the internal socio-economic conditions and political institutions in determining whether the economy in a given country could be transformed from a dependent export economy to an auto centric, nationally integrated economy.

From a number of country studies Senghass and Menzel extracted a list of conditions which, in Europe at least, could explain the occurrence or auto centric development. The important socio-economic variables included a relatively egalitarian distribution of land and incomes; a high level of literacy; and economic policies and institutions that supported industrialization and industrial interests. The political variables included extensive mobilization of farmers and workers; effective democratization to weaken the old elites; and partnership between the bureaucracy, industrial interests and the new social movements.

Senghass and Menzel, when they initiated their ambitious research programme, essentially wanted to find out how much could be learned from the over a century and a half of European experiences that would be of relevance to understanding the basic preconditions for the transformation of dependent, peripheral economies into auto centric economies.

There is little doubt that they have produced highly adequate documentation concerning he intra societal conditions, but here is also little doubt that their approach can be further enriched by more systematically taking into consideration the basic changes in the world capitalist system which have impacted heavily upon contemporary centre, periphery relationships.