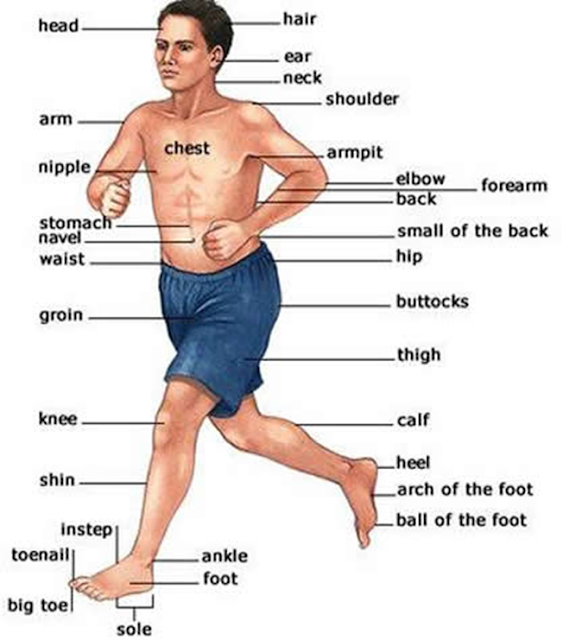

Theseexternal partsof human body are connected to the five major sense organs which tell us about our surroundings. All these parts are observable from outside, but they establish the connection between our internal part and external environment either mechanically or electrically.

The shape and size of the body parts differ from person to person. This makes us look different from one another. Thus, even in a crowded room, we can identify our friend easily. Men and women body parts are mostly alike, except for a few sexual differences. The following are main parts of ourbodyand some related components.

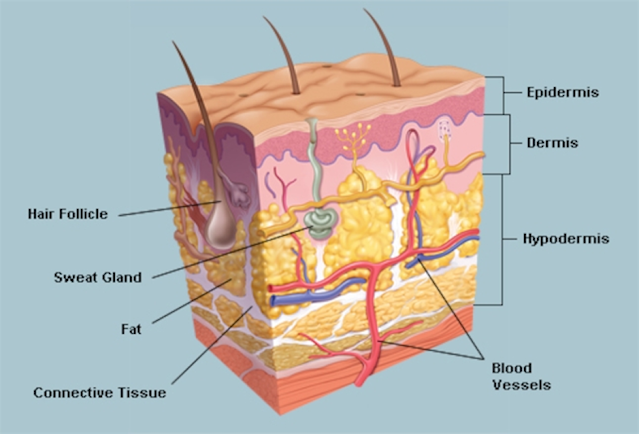

SKIN

Theskinis one of the most important parts of your body. It is also the largest organ of the body and helps the body in performing various different functions. One of the main functions of skin is that it provides a protective covering for the body and also protects all the organs inside. The skin, which is a semi-permeable membrane, allows nutrients to go inside, whereas it keeps all the undesirable things outside. It also helps in regulating temperature and excretion. Skin has three layers:

- The epidermis,the outermost layer of skin and the most resistant, provides a waterproof barrier and creates our skin tone.

- The dermis,beneath the epidermis, contains tough connective tissue, hair follicles, and sweat glands.

- The deeper subcutaneous tissue (hypodermis) is made of fat and connective tissue.

The skin’s colour is created by special cells called melanocytes, which produce the pigmentmelanin. Melanocytes are located in the epidermis.

The most common Skin Conditions include:

Rash:Nearly any change in the skin’s appearance can be called a rash. Most rashes are from simple skin irritation; others result from medical conditions.

Dermatitis: A general term for inflammation of the skin. Atopic dermatitis (a type of eczema) is the most common form.

Eczema: Skin inflammation (dermatitis) causing an itchy rash. Most often, it’s due to an overactive immune system.

Dandruff:A scaly condition of the scalp may be caused by seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, or eczema.

Acne:The most common skin condition, acne affects over 85% of people at some time in life.

Warts:A virus infects the skin and causes the skin to grow excessively, creating a wart. Warts may be treated at home with chemicals, duct tape, or freezing, or removed by a physician.

Herpes: The herpes viruses HSV-1 and HSV-2 can cause periodic blisters or skin irritation around the lips or the genitals.

Shingles (herpes zoster):Caused by the chickenpox virus, shingles is a painful rash on one side of the body. A new adult vaccine can prevent shingles in most people.

Ringworm:A fungal skin infection (also called tinea). The characteristic rings it creates are not due to worms.

Some of these Skin conditions can be addressed using Treatments, including the following:

Antibiotics: Medicines that can kill the bacteria causing cellulitis and other skin infections.

Antifungal drugs:Topical creams can cure most fungal skin infections. Occasionally, oral medicines may be needed.

Skin moisturisers (emollients):Dry skin is more likely to become irritated and itchy. Moisturisers can reduce symptoms of many skin conditions.

Apart from the skin which covers all parts, the main parts of human body are: head, neck, trunk and limbs. Each part has different functions and contains different organs. Whether we are walking, talking, sleeping, playing or sitting, our body is constantly working hard to keep us in full health. It is important to know our body in order to take care of it and live a long healthy life.

HEAD

The human head is the upper extremity of the body, connected by the neck to the trunk. It has an oval shape and it hosts the brain. On the front part called face, the head contains four sense organs: nose, eyes, ears and mouth. They all send sensation messages to the brain: the nose sends smells, the eyes send images, the ears send sounds and the mouth sends tastes. The following are the main features of our head and their functions.

Hair:Our hair is not only found on the head, but all over the body. The only areas on the body where hairs are not present are the palms of the hands, soles and the lips. Even if you cannot see the body hair on some parts of your body, there are no human body parts where hairs are not really present. The colour of the hairs may be very light, so much so that they almost seem invisible. Hairs are rooted in the second layer of skin. They are made up of a special kind of protein known as keratin.

Eyes:The eyes are a significant part of the body anatomy. There are three different layers that make up the human eyes. These are known as the vascular, nervous, and the fibrous tunic. The outermost layer of the eyes is known as the fibrous tunic. This layer is composed of the cornea and the sclera, which is the outermost protective layer. The middle layer consists of the irises, the ciliary body, and the choroids. The innermost part of the eye consists of the retina.

Ears:Our ears are one of the five sensory organs and allow us to hear sounds. The ears collect the various sounds in the environment and transmit the auditory signals to the brain. The ear is made up of three main sections: –the outer ear or the auricle, the middle ear, and the inner ear. Apart from collecting sounds and transmitting the signals to the brain, the ears are also known to help maintain the body’s balance.

Nose:The nose is one of the main organs of the respiratory system. The respiratory system is responsible for bringing in the oxygen from the environment, utilising it, and expelling the carbon dioxide. The nose is also essential for discerning various smells. The nose performs the most important of the respiratory system functions and that is to inhale air.

Teeth:The teeth are important and help in the digestion of foods. It is our teeth that help us chew food, allowing the digestive enzymes in the saliva to mix with the food.

Tongue:Tongue is a strong muscle that performs a different function than the regular muscular system functions. The tongue is covered with taste buds that help us discern various tastes.

NECK

When you study the body anatomy and organs, the neck comes across as a load bearing organ that connects the head to the rest of the body. Our neck is also very important because it attaches the base of the skull to the shoulders and the spine runs through it. Among the other functions of body parts, the neck provides movement to the head. It also sustains the head and helps it move up and down, left and right. Another important function of the neck is protecting the nerves that send sensory and motor information from the brain to the rest of the body.

Theshouldersare another load bearing joints that give us the erect stature and also attach the arms to the body. The arms are attached into the shoulder sockets and their movements are possible because of the shoulders. Below the shoulders lies the chest, stomach, waist, back and hips, which are part of the trunk.

TRUNK

The trunk is the body part that connects all the other parts and hosts many important internal organs such as: heart, lungs, stomach, liver, kidneys and reproductive organs that we shall detail in the next section.

LIMBS (LEGS AND ARMS)

A human being has four limbs: two arms and two legs. These limbs are what make the human body mobile. The arms end into hands, which, with their opposable thumbs, allow us to perform complex actions. The arms are the upper limbs, connected to the trunk in the superior side, one on the left and one on the right. The arm consists of: shoulder, elbow, forearm, wrist, palm and fingers. With the help of our arms we can catch, hold and carry objects.

- hand

- thumb

- index finger

- middle finger

- ring finger

- little finger

- nail

- knuckle

The legs, with the knees and the feet, carry our weight and help inlocomotion. The legs are connected to the trunk in the inferior side. The leg consists of: hip, thigh, knee, ankle, foot and toes. With the help of our legs we can walk, run and jump. The legs sustain the entire weight of the body and carry it where it needs to go.